June 3, 2023

How Much Does Divorce Cost in Georgia?

Abraham Lincoln once emphasized the value of a lawyer’s time when he said, “A lawyer’s advice is his stock in trade.” The value of the professional services of lawyers are not easily measured since legal matters differ widely and no two factual situations are exactly alike. Therefore, in most instances, the fee will depend upon the factors involved in the specific case at hand and cannot be determined by any pre-established general fee schedule. The elements most often considered include: (1) the time and labor required, the novelty and difficulty of the question involved, and the skill needed to perform the legal service properly; (2) the likelihood that the acceptance of the particular employment will preclude other employment by the lawyer based upon the fact that he or she has accepted responsibility to handle your case rather than other cases; and (3) the experience, reputation, and ability of the lawyer or lawyers, performing the services.

Our firm endeavors to bill our clients a fairly and ethically. Our clients must understand, however, is that as professionals in the legal world we are selling our TIME. Our time may be invested meeting with clients, litigating in the courtroom, preparing for court, representing clients at mediation, or sending and responding to emails from clients, opposing counsel, judges, clerks of court, witnesses or a number of other third parties. We are committed, however, to taking any and all actions necessary to prevail and to obtain the results that our clients hope to achieve without engaging in billable activities that do not benefit the client.

I have been practicing family law in the Griffin, Flint, Coweta and Towaliga Judicial Circuits for nearly 28 years. My current hourly rate is $300 per hour. Over the past few months I have litigated cases against opposing counsel in the area with similar levels of experience who both billed their time at $450/hr. I recently undertook a case against a larger family law firm from outside of the area. The senior attorney handling the case bills his time at $780/hr. (35 years’ experience). His associate attorney assisting him with the case is billing his time at $400/hr. (8 years’ experience). Their paralegals and secretaries that work on the case bill their time at $250/hr.

Lawyers.com is a website that provide legal information to the public. In 2020 I came across an informative article that might be a helpful read for anyone that is interested in this particular subject matter. How Much Does Divorce Cost in Georgia? | Lawyers.com

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Divorce Cost in Georgia

TYPICAL HOURLY FEES

On average, Georgia divorce lawyers charge between $250 and $300 per hour.

TYPICAL TOTAL FEES

Average total costs for Georgia divorce lawyers are $10,500 to $12,700 but typically are significantly lower in cases with no contested issues.

Our national divorce survey showed that more than two-thirds of people hire a lawyer to help with their divorce. When that’s the case, attorney’s fees accounted for the bulk of the cost of divorce. In order to understand the results of our study, it’s important to remember the two elements that determine an attorney’s total bill: the hourly rate and the number of hours required to resolve all of the issues in the case. We examined how both of those factors play out in Georgia divorces.

The attorneys in our study reported the range of hourly rates they charge clients. The average minimum across Georgia was $250 per hour, and the average maximum was $300 per hour. This range is close to the national average rates for family lawyers, and it’s significantly lower than typical hourly rates in expensive states like New York and California.

In addition to the differences between states, you may encounter hourly rates at the upper or lower end of the range (or outside of it) for various reasons, especially:

- Location within Georgia. Attorneys with offices in big cities with a higher cost of living usually charge higher hourly rates than their counterparts in smaller towns. And because so many lawyers are concentrated in those big cities, they tend to skew the statewide average upward. So you might find that lawyers outside of the greater Atlanta-Sandy Springs metropolitan area have somewhat lower rates than the statewide averages.

- Family law expertise. Attorneys with years or decades of experience—especially those who specialize in family law—generally charge more per hour than lawyers who are new to the field or have a general law practice. But in this case, it’s worth pointing out that higher hourly rates don’t necessarily lead to higher total bills, because it will often take a seasoned family law specialist relatively less time to resolve difficult issues that come up in a divorce case.

What’s the Typical Total Cost for a Georgia Divorce Lawyer?

Our survey also revealed that the vast majority of readers who hire divorce lawyers choose what’s known as full-scope representation—meaning that the attorneys take care of everything in the case, rather than only limited tasks like reviewing a settlement agreement. So when we examined total expenses in typical Georgia divorce cases, we focused on the expense of a full-scope attorney.

Once we analyzed the combined data from our reader survey and attorney study, the results showed that the average total cost of a full-scope attorney in a typical Georgia divorce ranges from $10,500 to $12,700, based on minimum and maximum hourly rates. However, your expenses could be significantly higher or lower than that range, depending on the contested issues in your case and whether you’re able to settle those disputes without going to trial.

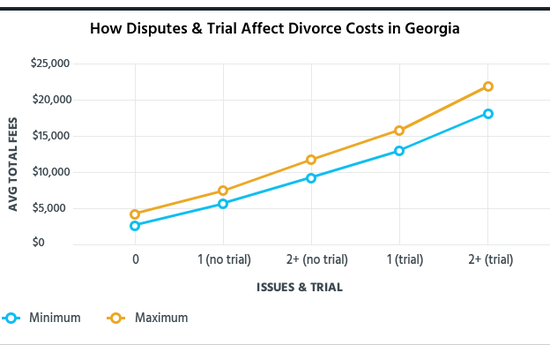

How Disputes and Trial Affect the Cost of Divorce in Georgia

In our survey, at least 85% of readers disagreed with their spouses about at least one of the significant issues that arise in divorce, such as:

Because it takes time for your lawyer to resolve these disputes, they can have a big impact on the total cost of your divorce. First off, the attorney will need to spend time on discovery.. This evidence-gathering process includes collecting and exchanging financial documents and conducting depositions. If your spouse doesn’t cooperate with discovery, or if one of you requests a temporary order for support or custody, more time will be required to prepare motions and attend court hearings on the matter. Also, it takes time to negotiate a settlement—and even more time to prepare for and represent you in a divorce trial if negotiations don’t lead to a settlement agreement on all of the contested issues.

We drilled down into our survey results and attorney study to learn just how much contested issues affect divorce costs in Georgia. Our analysis showed that in cases when couples have no disagreements about significant issues, the average total cost of divorce is $3,700-$4,600. When couples have one dispute but settle it without a trial, average costs are $5,500-$6,600. In comparison, average costs are $13,000 to $15,700 if they go to trial on the dispute. Two or more contested issues raise average expenses to $9,500-$11,500 if they reach a settlement on all issues and $17,700-$21,500 if they need a trial to resolve multiple disputes.

The Impact of a “Fault” Divorce on Costs

In Georgia, you can file for a “fault” or a “no-fault” divorce. For a no-fault divorce, you simply claim that the marriage is “irretrievably broken,” which basically means that there’s no hope of reconciliation. For a fault divorce, you must accuse your spouse of one of the “grounds” (or reasons) for divorce listed in Georgia law, including:

- adultery

- cruel treatment

- willful desertion for at least a year

- habitual intoxication, or

- conviction for a crime involving “mortal turpitude” (with a prison sentence of at least two years).

Fault divorces are usually more expensive, because it takes time for your attorney to come up with evidence proving the claims of misconduct (or countering them, if you’re the one accused of misconduct). In addition, your lawyer might have to hire outside experts like private investigators.

In Georgia, judges may consider a spouse’s misconduct during the marriage when awarding alimony or dividing the couple’s property. They may also take into account any evidence of domestic violence or a parent’s substance abuse when they’re making decisions about child custody. But even in a no-fault divorce, a judge might consider some types of misconduct, such as whether a spouse’s gambling problem depleted the couple’s assets. So if you’re considering filing a fault divorce, you should speak first with an attorney who can evaluate your situation and help you decide whether it would be worth the additional expense.

What Other Expenses Contribute to the Cost of Divorce?

Besides what you pay your attorney—and even if you don’t hire a lawyer—you will have other expenses in your divorce. First off, there are filing fees, which can vary from county to county in Georgia, as well as fees to have papers served on other spouse. You might also have to pay fees for experts like child custody evaluators, financial analysts, or even forensic accountants if you believe your spouse is hiding assets or income. Readers in our national survey reported paying an average of $1,600 for these non-lawyer expenses. As with attorneys’ fees, your costs could vary widely depending on the nature and number of disputes in your divorce.